Can We Afford Not to Have Another Kid?

Why raising children is still the most important investment we can still make.

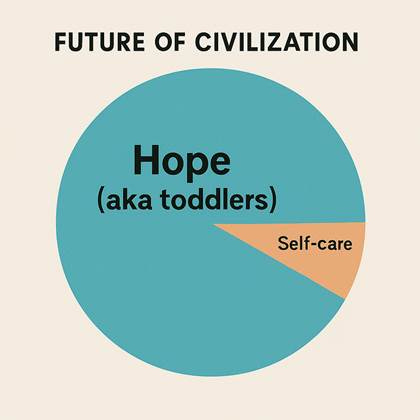

Welcome back to this two-part series on the cost - and calling - of adding children to a family in today’s world. These posts aren’t opposites, but bookends: the first makes the economic case for hesitation, while today’s makes the case for children as our best hope.

Each holds, in my mind anyways, a piece of truth. Taken together, they reflect the tension families live in every day - between what’s practical and what feels essential. This second post turns toward the why, and what it means to choose growth anyway.

Can We Afford to Not Have Another Kid?

I just made the case for why having more kids is so hard - and all of it is true. But now, I need to make the case for why it still matters. Even knowing the cost, I feel pulled by something bigger than the balance sheet.

Because the truth is: we don’t just want more kids. We need them.

A Nation of Fewer Cribs and More Crises

The U.S. birthrate is about 1.6 - well below the replacement rate of 2.1. That sounds like a technicality - but it’s a flashing red light. A shrinking population doesn’t just mean fewer babies. It means fewer workers, fewer taxpayers, fewer future caregivers.

And for better or worse, many of our systems - Social Security, school funding, housing markets, even how we plan roads and cities - are designed with growth in mind. Take that growth away, and the cracks start to show. School districts consolidate. Industries face worker shortages. The cost of supporting retirees rises faster than the labor force that funds them.

Countries like Japan and South Korea are already living this reality. Their populations are aging and shrinking. Their economies are stalling. Their governments are throwing money at the problem - but once a society tips into long-term decline, it's hard to reverse.

The U.S. still has time. But not much.

The AI Babysitter Isn’t Ready Yet

Time for some economic context (the best kind of context).

The Congressional Budget Office projects slower economic growth over the next 30 years, driven largely by weak population growth. By 2055, our publicly held debt is projected to hit 156% of GDP. Labor force participation is weakening. GDP growth is projected to hover around 1.9%.

Meanwhile, Social Security is on track to deplete its trust funds by 2035. At that point, unless something changes, retirees will receive only 77% of their scheduled benefits. All of this is tied to population. Fewer people entering the workforce means fewer people paying into the system.

Our entitlement programs, labor markets, and tax revenues all depend on generational renewal. Some people say: don’t worry, AI and automation will pick up the slack. While I’m sure ChatGPT 17.0 will be great at changing diapers, forgive me for not trusting every promise that comes out of Silicon Valley.

Yes, there will be real productivity gains from AI & robotics. But we can’t put all our eggs in that basket and hope for the best. If we do nothing, and those gains don’t arrive fast enough or widely enough, we’ll be jumping for an economic trapeze with no safety net.

Diapers Are Infrastructure

These economic realities stand in stark contrast to how kids are looked at by American society. We’ve framed children as a personal lifestyle choice, not a public good. That needs to change. Like it or not, children grow up to become workers, taxpayers, caregivers – they are the ones who carry everything forward.

When we talk about investing in the economy, we regularly focus on roads, energy grids, and defense budgets, all for good reason. But the most foundational investment a society can make is in the next generation of people who will sustain, improve, and inhabit it.

More children means more future builders, caregivers, and neighbors. It means more hands to help and more minds to innovate. And yes, more hearts to love and be loved.

The Richest People I Know? They Have Kids

Parents often aren’t the wealthiest when it comes to assets. But in my experience, they are the richest in meaning.

Having kids doesn’t guarantee happiness, but it reshapes how you see the world. Kids pull you out of yourself. They reorient your ambitions, reset your priorities, and remind you daily of what actually matters.

They make you more patient, more generous, and more resilient. They give you something to build toward, not just escape from. And when the world feels unsteady, they anchor you in the long game.

There’s a kind of wealth that doesn’t show up on a spreadsheet. It shows up in bedtime stories, school projects, family traditions, and dreams of the future. It those kind of characteristics that lead to a better world.

Building a Better World Starts at Home

You might notice where this is leading - the same place the last post led to: policies that are designed to support families in having kids. The economics make the case, but so does the heart. And both point in the same direction.

We need to start having real conversations - urgently - about what it would look like to make family growth more feasible and less precarious. That means revisiting ideas like expanding child tax credits, reducing the cost of childcare, and establishing meaningful paid family leave so that both parents can be present without financial strain.

It also means addressing the cost and availability of housing, particularly for families who need more space but can’t afford to move. It means addressing a culture that happily presents children as a universal good until the moment they become inconvenient. These aren’t abstract policy debates - they’re about creating a world where the choice to have a child doesn’t feel like a gamble.

None of these steps alone will solve everything, but together they could shift the balance. And if we care about the next generation, then those are the conversations we need to be willing to have now.

Some might find this naive. But I know the cost of raising a child. I’ve written about it. I live it. But I also know what it's worth. I want to invest in something that will outlive me. I want to contribute to a future that isn’t defined by shrinking expectations or deferred dreams.

Yes, we need to build better support systems for parents. We need to make it easier, more sustainable, and less isolating. But even before that happens, my wife and I are choosing growth. Because hope multiplies when it has a name, a heartbeat, and a place at the table.

Saying Yes to the Next Generation

In an age where we are constantly told to downsize our expectations and delay anything that might disrupt comfort, choosing to grow your family can feel radical. But it’s also a quiet kind of rebellion - a declaration that the future is still worth building.

We can’t plan our way out of every risk. But we can choose which risks are worth taking. And I believe this is one of them.

Sometimes, it’s sticky. Sometimes, it’s loud. Sometimes, you’ll spend an unsettling amount of time talking about poop. But to raise a child is to invest in a better tomorrow - not just for your own family, but for the country, the community, and the culture that child will inherit.

Right now, it’s hard. Right now, it’s costly. But some things are worth more than what they cost. And for me, more children is one of them. We can’t just want to have more kids. We need to have more kids.

I sincerely wish I had been able to read this post back in 2023 when we were deciding whether to add a second kid to our family! So many important value-gains*; only in capitalism would we overlook or dismiss them because the value isn't financial.

*noting that the benefits in terms of life satisfaction, happiness, meaning, etc. only show up in the research consistently for people who sincerely wanted kids, and I definitely don't mean to imply that all people everywhere should choose to reproduce—just that if the decision is about value, it's a shame the value that often wins out is economic.

I know just what you mean - before my son was born, I looked at it so much through the lens of financial stability. It was only after he arrived that the other values began to shine through, and there just isn't a great way to quantify that for would-be parents.